Financial Modeling for Startups: What Investors Expect to See

A financial model tells investors more than you think.

It shows how you understand your business, how you make decisions, and how you plan for growth. Most startup financial models fail not because the numbers are wrong but because they are disconnected from how the business actually works.

For tech startups, financial modeling is not a formality. It is how founders turn a product vision into an investable story. Investors don’t expect complex spreadsheets filled with macros and formulas.

They expect logic, transparency, and a clear link between product, users, and revenue.

They look for realistic assumptions about growth, cloud costs, and hiring. They expect to see that the founder understands margins, scalability, and cash flow — not just optimism.

This article explains what investors expect to see in a startup financial model today. It covers the structure, key assumptions, and benchmarks that matter for tech startups, from SaaS to AI and Fintech.

TL;DR

Topics covered in this article

- What Investors Expect From a Financial Model?

- The Core Structure: Simple, Logical, and Linked

- Revenue: The Story Investors Care About

- Cost of Revenues: Where Margins Are Made or Lost

- Operating Expenses: The Test of Discipline and Scalability

- Capital Expenditure and AI Infrastructure: Investment vs. Expense

- Cash Flow and Runway: Where the Model Becomes Real

- Models as Strategy: How Great Founders Use Financial Models

- Why Startups Choose Finro to Build Their Financial Models?

- The Financial Model Is the Language of Serious Founders and Serious Investors

- Key Takeaways

- Answers to The Most Asked Questions

What Investors Expect From a Financial Model?

Investors review hundreds of startup financial models each year. Most look the same: long spreadsheets with short explanations. What stands out is not complexity but clarity. A strong financial model tells investors that the founder understands how the business operates, scales, and generates returns.

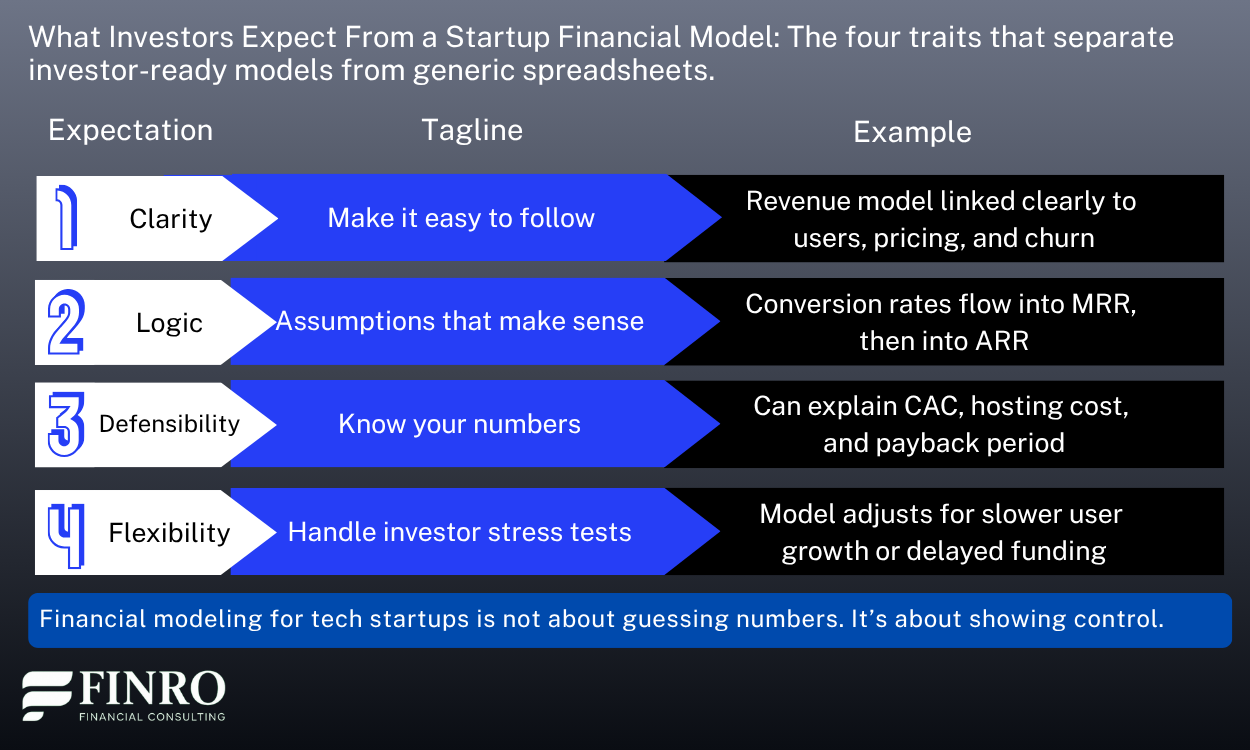

For tech startups, investors focus on four main qualities:

1. Clarity

A good financial model lets anyone understand the business in minutes. Revenues, costs, and cash flow should be clearly linked. If an investor needs a call to figure out how you make money, your model is not ready.

2. Logic

Every number should follow a clear path. If user growth drives revenue, it should connect through pricing, churn, and conversions. If you forecast headcount, it should match your hiring plan. Logical structure builds trust.

3. Defensibility

Investors expect founders to stand behind their assumptions. They will ask how you calculated customer acquisition cost, gross margin, or hosting expenses. If you can’t explain them confidently, they assume the model is a guess, not a plan.

4. Flexibility

A startup financial model should respond easily to changes. Investors test how the business performs if growth slows, margins tighten, or funding comes later than planned. The best models are designed to handle those scenarios without breaking.

Financial modeling for tech startups is not about impressing investors with size or speed. It is about showing how every assumption connects to your market, your product, and your path to profitability.

Next, let’s look at the core structure investors expect to see in a professional startup financial model — from revenue to cash flow — and how each part helps build investor confidence.

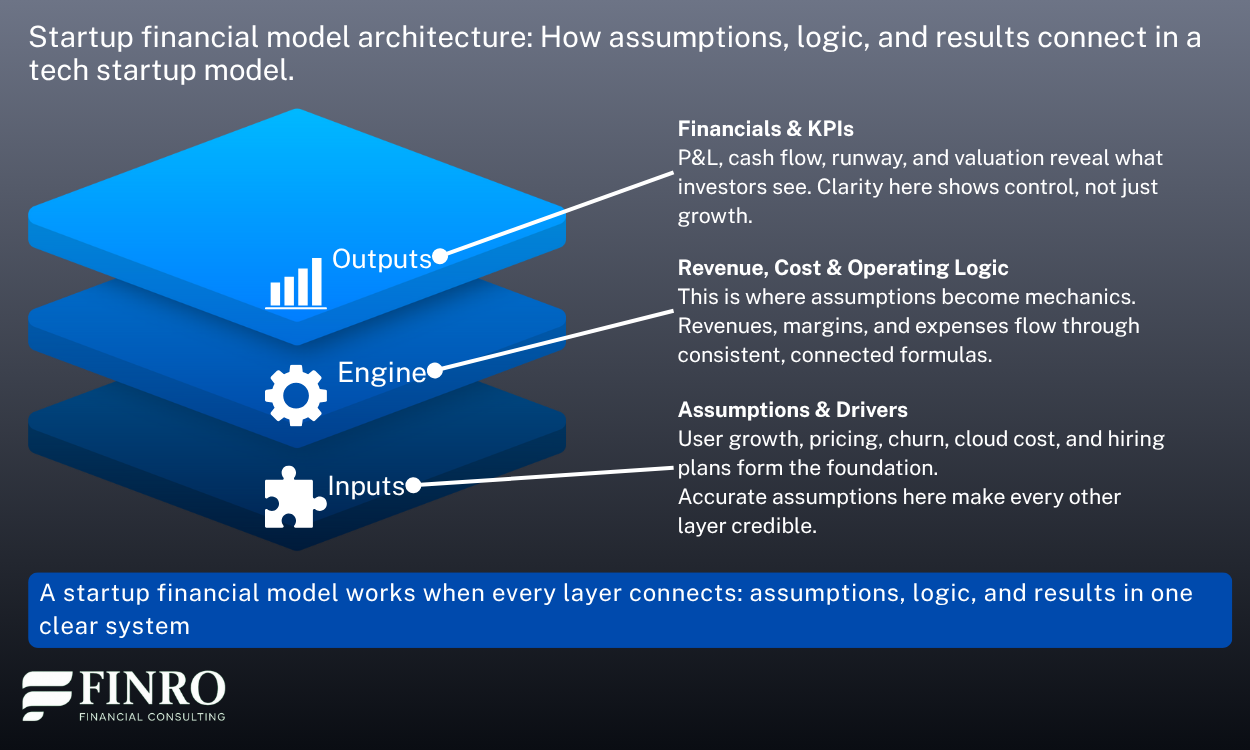

The Core Structure: Simple, Logical, and Linked

A professional startup financial model reads like a system, not a set of disconnected tabs. Think in three layers that flow left to right: inputs, engine, outputs.

Inputs hold the assumptions that describe how a tech product grows and what it costs to serve customers. Traffic, conversion, pricing, churn, usage intensity, cloud rates, and headcount plans sit here. Keep these assumptions visible and editable, with version notes and clear units.

Monthly granularity for the first 24–36 months supports hiring plans, seasonality, and GTM ramp. After that, a quarterly or annual roll-up keeps the file lean.

Engine is where assumptions become mechanics. The revenue engine converts users or transactions into MRR, ARR, or take-rate revenue. The cost engine converts usage into cloud spend, API tokens, GPU hours, payment fees, and support workload.

The operating engine maps roles and salaries to hiring dates, benefits, and productivity, then connects marketing spend to acquisition and expansion. Each sub-engine should reference shared dimensions like product lines, segments, and regions so the math stays consistent as the business scales.

Outputs present the story investors care about. The model should push a single set of linked statements: revenues and cost of revenues that create realistic gross margins, operating expenses that reflect a credible team plan, and a cash flow that ties profit to runway through working capital and capex. A funding schedule anchored to milestones makes the raise amount feel earned rather than arbitrary.

Two cross-cuts keep this structure investor-ready.

First, scenario control that switches the model across base, upside, and downside without breaking references.

Second, integrity checks that flag broken links, circular logic, or margins that fall outside sector norms. Together, they signal that the founder manages numbers with the same care used to manage the product.

When this architecture is right, a single tweak to conversion or pricing ripples through margins, hiring, and runway without manual fixes. That is what investors expect to see: a model that behaves like the business.

Next, we will open the revenue engine and show how to translate product, pricing, and user behavior into a forecast that investors trust.

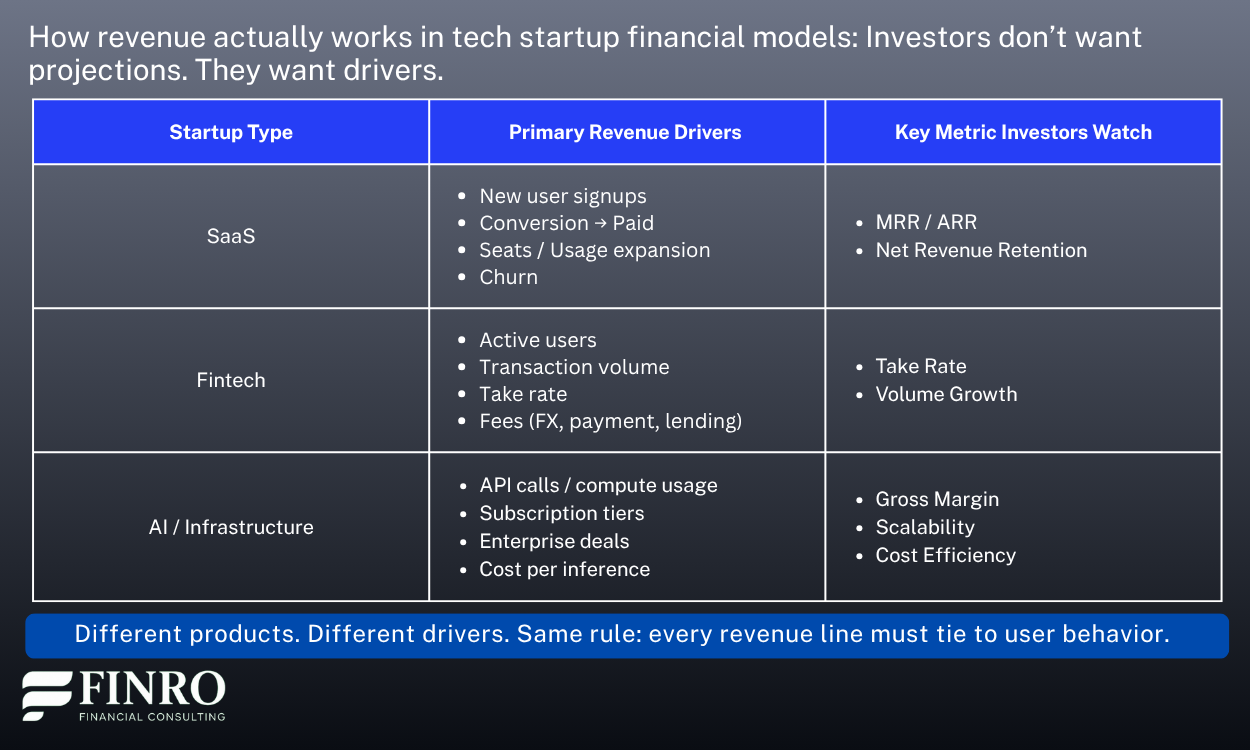

Revenue: The Story Investors Care About

Revenue is the heartbeat of every startup financial model. For investors, this is where the story either makes sense or falls apart. They expect to see a clear, defensible connection between what you sell, how you sell it, and who pays for it.

A good financial model for a tech startup doesn’t start with a target number. It begins with logic.

Revenue should flow from real drivers: user acquisition, pricing, usage, or transaction volume. The model needs to reflect how the product grows in the market, not how the founder hopes it will.

For SaaS startups, that logic usually starts with user cohorts, conversion rates, and churn. Revenue should scale through expansion (upgrades or additional seats), not just new signups. Monthly recurring revenue (MRR) and annual recurring revenue (ARR) are the core metrics investors use to assess predictability and retention.

In Fintech, the model often ties revenue to transaction volume and take rates. Investors want to see how growth in active users or payment volume translates into top-line growth. They also look for sensitivity: how small changes in fees or volume impact gross margins.

In AI and infrastructure startups, revenue modeling gets more complex. Some use API-based pricing, others combine subscriptions and usage fees. Investors expect transparency about cost of inference, compute pricing, and how scaling affects margins. Overlooking these details raises doubts about scalability.

Across all tech verticals, the best startup financial models follow one simple rule: every revenue line must have a driver you can measure. If an investor can’t trace a number back to a business action, a customer, a price point, or a usage metric, it doesn’t belong in the model.

Revenue is where investors test credibility. It shows whether your growth narrative is grounded in unit economics or built on optimism.

Next, we’ll look at cost of revenues, the part of the model that turns growth into margins and shows how efficiently your startup can scale.

Cost of Revenues: Where Margins Are Made or Lost

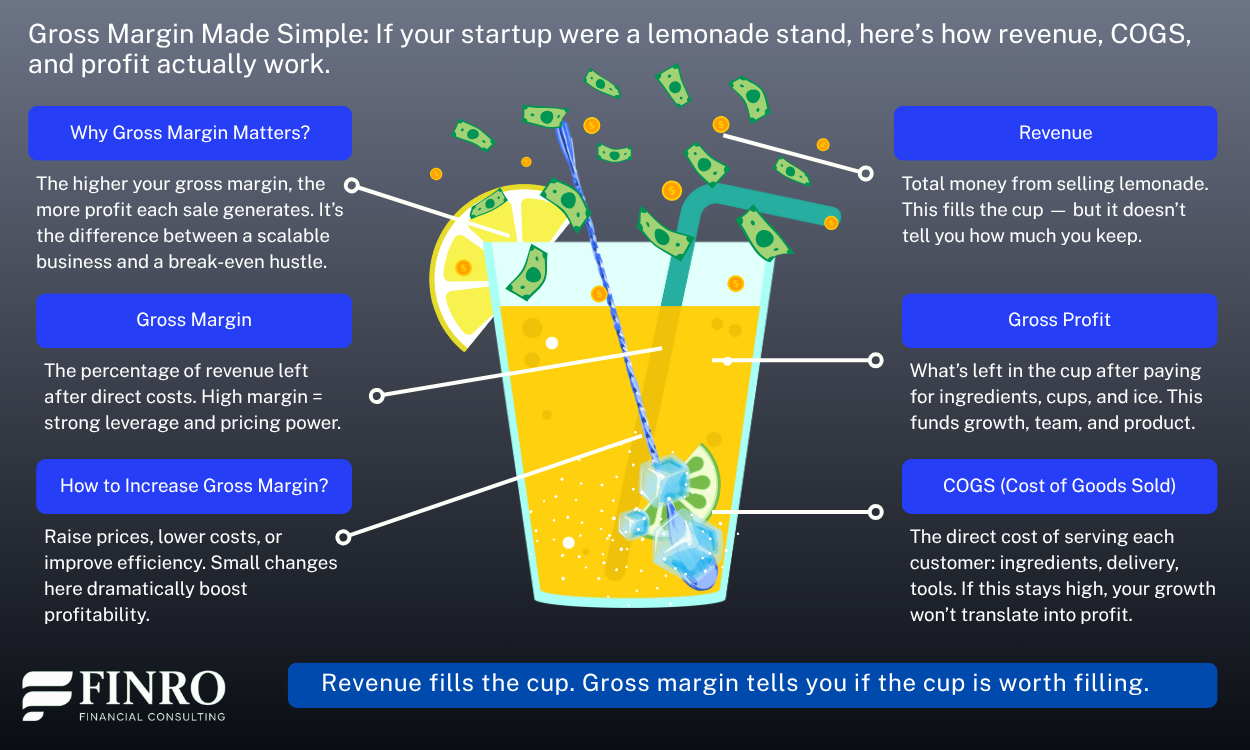

Revenue tells the growth story, but cost of revenues reveals whether that growth is sustainable. This is the part of the startup financial model where investors test reality. If your top line scales but your margins collapse as you grow, the model fails, no matter how impressive your revenue forecast looks.

For tech startups, cost of revenues (COGS) is not a generic percentage. It is a direct reflection of product architecture, infrastructure choices, pricing model, and customer behavior. Investors expect this section to show that you understand the real cost of serving each unit of revenue.

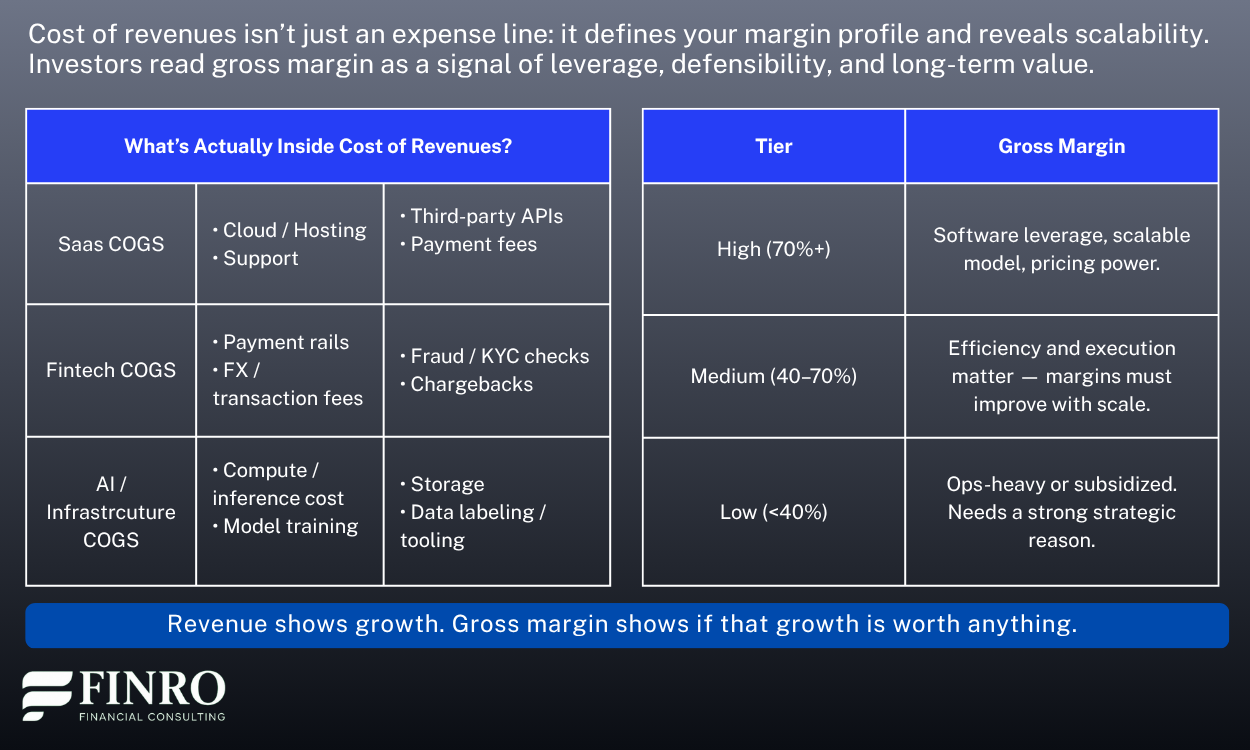

In SaaS, COGS often includes cloud hosting, third-party integrations, support, and payment processing. Mature SaaS companies improve gross margins over time through economies of scale and automation. If your model keeps margins flat or unrealistically high, investors will assume the math is off or the product can’t scale.

In Fintech, COGS is heavily transaction-driven. Payment rails, FX fees, fraud prevention, KYC/AML checks, and chargebacks all sit here. Take rate means nothing if your processing costs grow just as quickly. Investors focus on unit economics: how much do you earn per transaction after direct costs?

In AI and infrastructure startups, this layer is even more critical. Compute, storage, inference cost per request, and model training are expensive and variable. If you do not show how usage impacts cost and how margins improve as volume increases, investors will question the entire business model. They’ve seen too many AI startups with 90% gross margins in pitch decks and 30% in reality.

Strong financial modeling for tech startups treats cost of revenues like a dynamic system. Assume it changes as volume, product mix, or usage patterns evolve. Model tiered pricing, volume discounts, and efficiency gains over time. Show how margins improve as you scale — or explain why they won’t, and why that’s still a viable business.

Growth without margin is not growth. It is burn.

Investors don’t just look at how much you make, they look at how much you keep.

Next, we’ll break down operating expenses, where investors look for discipline, scalability, and the founder’s ability to manage resources as the company grows.

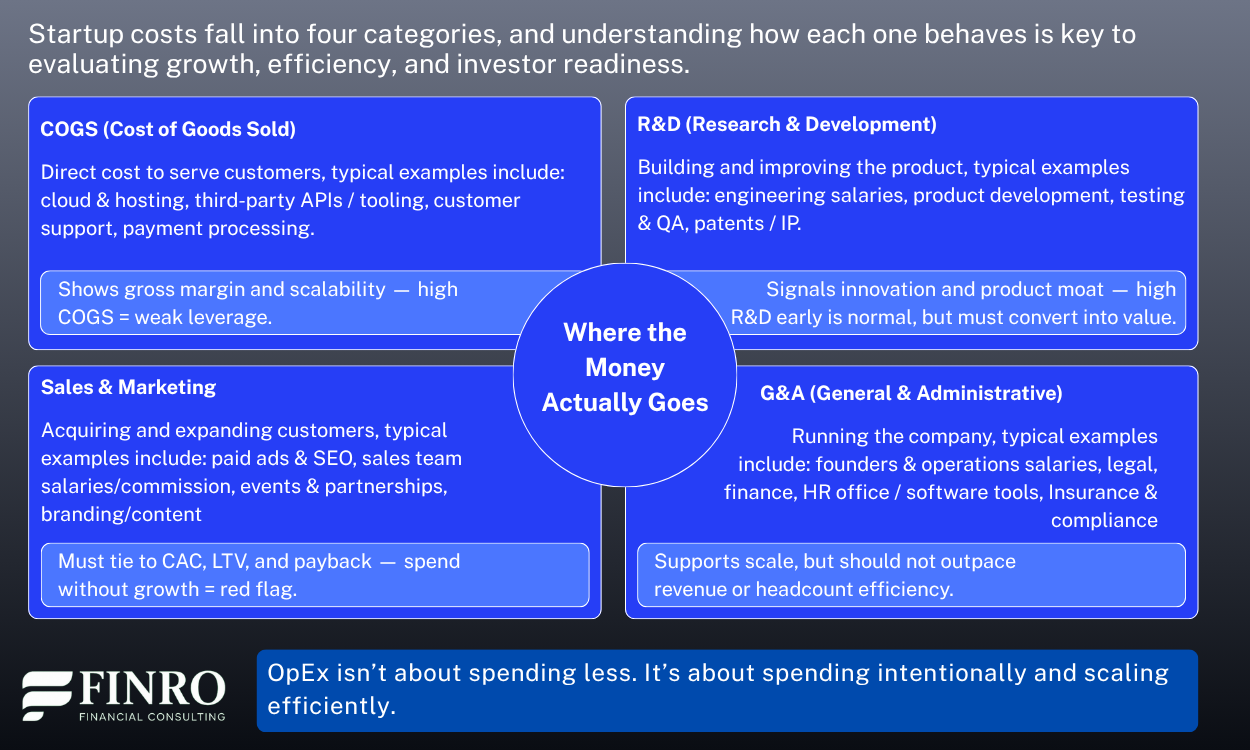

Operating Expenses: The Test of Discipline and Scalability

Revenue shows potential. Gross margin shows business model quality.

Operating expenses reveal the founder’s judgment.

Investors study operating expenses (OpEx) to understand how a tech startup allocates resources, builds capabilities, and scales responsibly. This section of the financial model isn’t just about what you spend — it’s about why, when, and how that spend converts into growth.

A strong startup financial model doesn’t apply “% of revenue” shortcuts. It builds OpEx from the ground up: headcount, salaries, hiring timelines, tools, marketing programs, and product development. Investors don’t expect low spending — they expect intentional spending tied to milestones and strategy.

Headcount is the biggest signal of founder thinking.

The model should reflect how teams grow over time: roles, start dates, and compensation aligned with product and GTM plans. If revenue doubles but headcount stays flat, investors know the model is unrealistic. If headcount explodes before product-market fit, it signals a burn problem.

Marketing and sales spending must link back to revenue drivers.

CAC, payback period, and conversion funnel logic need to match the revenue model. Dumping a lump-sum marketing budget into the model without showing how it generates users is a credibility killer.

Modern OpEx also reflects the shift in tech operations.

AI tools reduce some roles but introduce new SaaS costs. Remote teams change salary benchmarks but increase spend on tooling and collaboration platforms. Great models reflect these shifts, not outdated office-based structures.

The key question investors ask is simple:

Does spending scale linearly, or does the business unlock leverage over time?

A disciplined OpEx structure shows that the founder understands sequencing, efficiency, and the difference between investment and waste. When headcount, tooling, and GTM spend are tied to specific growth milestones, the financial model stops being a budget — and starts being a plan.

Next, we’ll look at capital expenditure and AI infrastructure, where tech startups often misclassify investment vs. expense — and where hidden value can be created or destroyed.

How Operating Expenses Should Evolve As a Startup Scales?

| Stage | Spending Focus | Why | Investor Lens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Stage / Pre-PMF | R&D heavy, everything else lean | Building product and validating the problem. Sales & marketing minimal. G&A scrappy. COGS depends on prototype usage. | High R&D is normal. Low burn elsewhere signals discipline. |

| PMF / Early Growth | Balanced R&D + emerging sales & marketing | Product is working. Start investing in acquisition. R&D shifts to iteration. G&A grows with team. | Sales & marketing spend must tie to CAC, LTV, and payback. |

| Scale / Expansion | Sales & marketing becomes largest cost driver | Growth accelerates. GTM becomes the engine. R&D stabilizes or supports new product lines. G&A must support scale efficiently. | Growth is expected, but efficiency and margin improvement matter. |

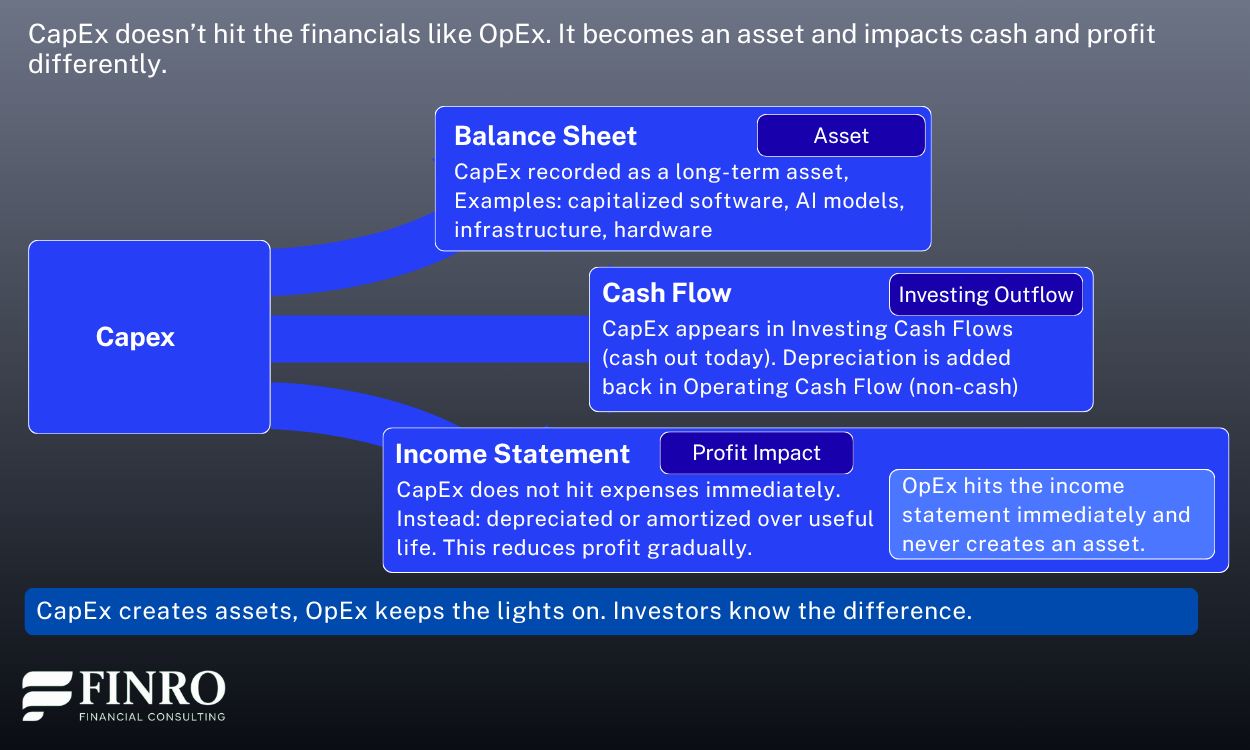

Capital Expenditure and AI Infrastructure: Investment vs. Expense

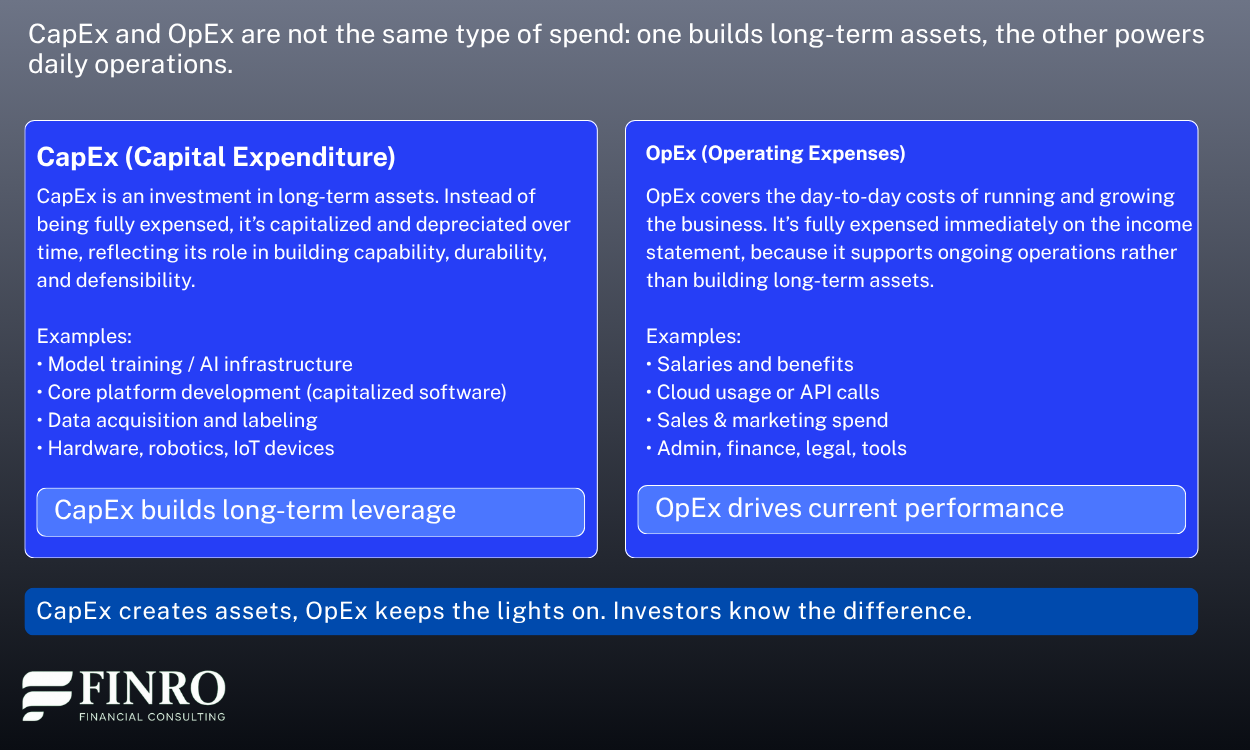

Most early-stage startups treat capital expenditure (CapEx) as an afterthought. In traditional software businesses, that approach was often fine, nearly everything was OpEx. But in modern tech startups, especially AI, infrastructure-driven, or hardware-enabled models, CapEx can be the difference between a scalable asset and a never-ending expense.

Investors don’t just ask how much you spend.

They ask what you’re building when you spend.

CapEx represents long-term investment.

This includes things like:

Building core technology or platforms

Model training infrastructure

Data acquisition or labeling at scale

Hardware, robotics, or IoT devices

Capitalized software development or IP

OpEx represents the cost to operate right now.

Salaries, cloud usage, tooling, marketing, admin, support — the engine of the business.

The mistake many founders make is putting everything into OpEx, which makes the business look more expensive and less scalable than it actually is. Investors understand that some spending creates enduring value, and they want to see that value captured correctly.

This matters even more in AI and infrastructure startups.

Training models, storing large datasets, or securing GPU capacity are not just “expenses.” They are core assets that drive defensibility and margin improvement over time. When these investments are modeled as CapEx, the financial model tells the right story:

“We’re building an asset, not just burning cash.”

Investors look for three signals here:

Is the company building durable IP or just renting compute?

Will the cost structure improve as the system scales?

Does the model separate investment from operations?

A clear CapEx strategy shows maturity. It signals that the founder understands the difference between spending to grow and spending to build value. In a startup financial model, that distinction directly impacts valuation, capital efficiency, and investor confidence.

Next, we’ll look at cash flow and runway, where investors test whether all of these assumptions, revenue, margins, OpEx, and CapEx, actually translate into a fundable, sustainable business.

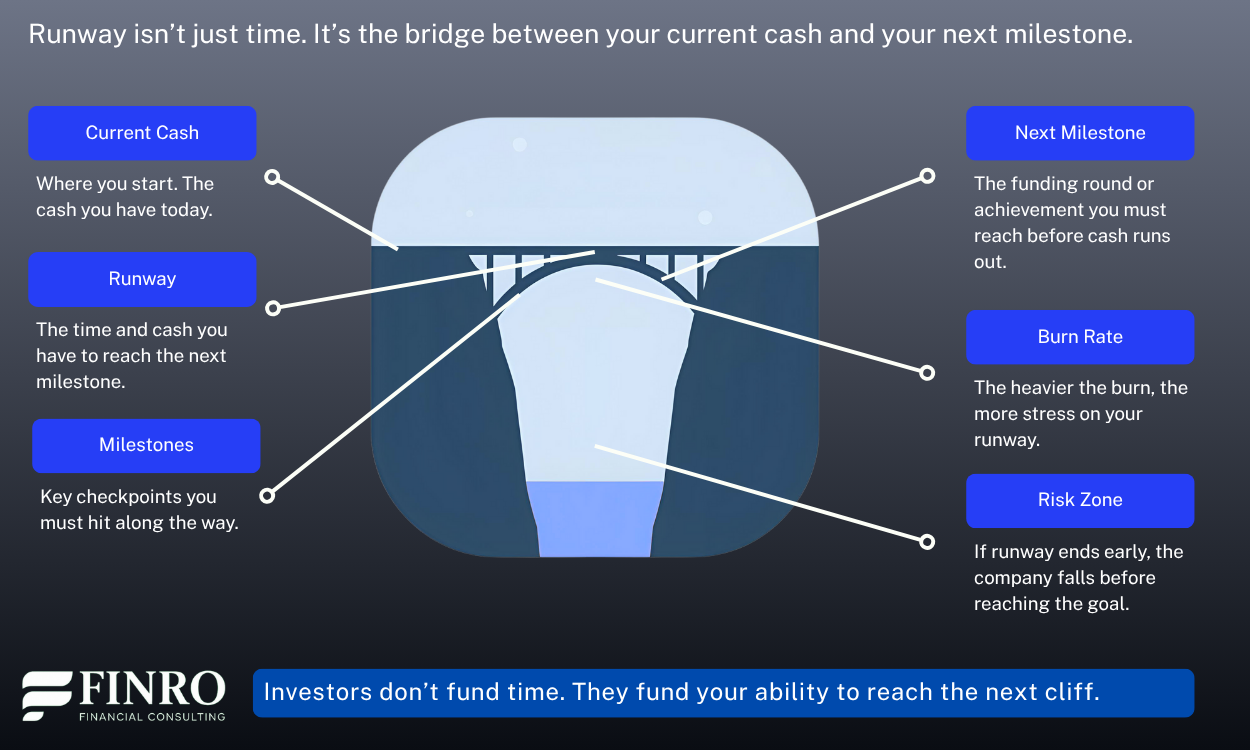

Cash Flow and Runway: Where the Model Becomes Real

Revenue, margins, and operating expenses tell the story of growth and efficiency — but cash flow shows whether the business can survive long enough to get there. This is the part of the financial model where investors stop looking at potential and start evaluating risk.

A tech startup can have strong revenue and even solid margins, yet still run out of cash because of timing, burn rate, or capital misalignment. That’s why cash flow and runway are the true stress test of a financial model.

Cash flow is not just Net Income in disguise.

Investors look at how cash actually moves through the business:

How long does it take to collect revenue?

Are payment terms delaying cash in?

Do cloud, vendor, or payroll costs hit before revenue?

Are you burning cash faster than you’re compounding growth?

Runway is not just “cash ÷ burn.”

Investors check if the startup understands the drivers of burn:

Headcount vs. tooling vs. cloud vs. GTM

One-time vs. recurring costs

Fixed vs. variable costs

Impact of scaling on future burn

They also want to see the runway aligned with milestones.

Twelve months of runway is meaningless if the next fundraising event requires 18 months of traction. The best models don’t just show “how long cash lasts” — they show what the company will achieve before cash runs out.

This is where scenario planning becomes mandatory.

Investors will change assumptions:

What if revenue is slower?

What if CAC is higher?

What if hiring slips?

What if the next round happens later?

A credible startup financial model can flex without breaking. It should clearly show how each scenario affects cash runway and how the business adapts.

Ultimately, investors don’t invest in projections.

They invest in founders who can manage capital.

A model that transparently connects burn rate, milestones, and funding strategy signals a founder who understands not just how to grow — but how to stay alive while doing it.

Next, we’ll shift from survival to valuation and look at how investors interpret the entire model to determine what your startup is actually worth.

Models as Strategy: How Great Founders Use Financial Models

Most founders treat the financial model as something investors ask for.

Great founders treat it as a strategic tool that drives every major decision.

A strong financial model is not just numbers in a spreadsheet — it is a living system that connects vision, execution, and capital. The best founders use it to think, operate, and communicate at a higher level.

Here’s how:

1. They turn goals into assumptions, not guesses.

Instead of starting with a revenue target and working backwards, great founders model the mechanics that produce growth: acquisition, conversion, retention, pricing, and usage.

Assumptions become actions — and actions can be tested.

2. They use the model to allocate resources deliberately.

Every headcount, marketing dollar, product sprint, and infrastructure cost is tied to performance or milestones.

The model becomes a filter for prioritization:

What moves the business forward? What can wait? What isn’t worth it?

3. They forecast scenarios, not single outcomes.

Investors will always ask “What if?”

Great founders already know:

What if growth slows?

What if margins improve?

What if we delay hiring?

What if we raise later — or earlier?

A model that flexes shows control — and reduces risk.

4. They use the model to align the team.

Teams move faster when they understand the financial logic behind decisions.

A model makes strategy transparent:

Why we’re hiring these roles

Why we’re entering this market

Why we’re raising this amount of capital

The model becomes the operating system of the company.

5. They build investor confidence before the pitch.

When a founder understands every assumption, driver, and tradeoff in the model, investors don’t just believe the numbers — they trust the founder.

A credible model signals:

I understand how this business scales.

I know what it takes to get there.

Great founders don’t build models to impress investors.

They build models to run the business — and investors see the difference.

| Average Founders... | Great Founders... |

|---|---|

| Build models only when investors ask | Build models early to make better decisions |

| Start with revenue targets | Start with assumptions and drivers |

| Use one static forecast | Build multiple scenarios |

| Treat all costs the same | Allocate capital based on milestones and ROI |

| Use the model as a reporting tool | Use the model as an operating system |

| Focus on “what we need to raise” | Focus on “what we can achieve with capital” |

| See the model as finance | See the model as strategy |

Why Startups Choose Finro to Build Their Financial Models?

Most financial models are built to satisfy a request.

We build them to win investor confidence, guide decisions, and scale companies with clarity.

Founders work with Finro because we don’t just “fill in a template.”

We combine deep financial expertise with real startup experience to build models that investors trust and teams actually use.

Here’s what sets Finro apart:

1. We build models the way investors review them.

We’ve seen hundreds of investor conversations and due diligence processes.

We know what VCs, growth equity, and strategic buyers look for — and what raises red flags.

Our models make it easy for investors to say “yes.”

2. We go beyond spreadsheets — we design the growth engine.

We don’t just model the numbers.

We build the logic behind acquisition, pricing, churn, expansion, headcount, infrastructure, and margins.

Founders get clarity on how the business actually works and how it scales.

3. We tailor models to your sector.

SaaS, Fintech, AI, marketplaces, infrastructure — each has different revenue mechanics, cost structures, and investor benchmarks.

We don’t generalize. We model reality.

4. We combine financial rigor with operational insight.

We understand both sides of the table — and build models that satisfy both.

5. We turn the model into a strategic tool for the founder.

We don’t hand over a file and disappear.

We help founders use the model to:

Allocate capital

Build hiring plans

Set milestones

Pressure-test scenarios

Prepare for fundraising conversations

The model becomes the operating system — not just documentation.

6. Our models survive investor diligence.

When investors push, our models hold up.

They’re logical, transparent, defensible, and built to be stress-tested.

Founders look prepared. Investors gain conviction.

Startups don’t choose Finro just to “build a model.”

They choose Finro to gain clarity, credibility, and a financial foundation built for scale.

The Financial Model Is the Language of Serious Founders and Serious Investors

A great financial model is not a spreadsheet.

It is the most complete expression of how a startup grows, allocates resources, manages risk, and creates value.

When it’s built well, a model becomes:

✅ A strategy tool — turning vision into assumptions, mechanics, and milestones.

✅ A decision-making engine — guiding hiring, pricing, spending, and timing.

✅ A signal to investors — showing growth quality, margin strength, capital efficiency, and founder clarity.

✅ A runway and valuation map — revealing not just how long you can operate, but how far you can go.

Founders who treat modeling as a formality stay reactive.

Founders who treat it as infrastructure build with intention — and earn investor conviction.

In the end, the financial model answers the only question that matters:

Can this business scale — and can this founder lead it there?

If the model says yes, everything else becomes easier: raising capital, aligning teams, making decisions, and building a company that lasts.

Ready to build a model that investors trust and founders actually use?

Let’s build it together.

Key Takeaways

1. Financial models are strategic tools: They guide decisions, align teams, and shape how founders plan growth—not just satisfy investor requests.

2. Revenue must be driver-based: Investors expect forecasts tied to acquisition, pricing, usage, retention, and expansion—not top-down guesses.

3. Margins signal scalability: Cost of revenues and gross margin quality reveal product leverage, efficiency, and long-term business model strength.

4. Cash flow and runway show reality: Runway depends on how cash actually moves, burn rate, and the ability to reach the next milestone on time.

5. Great founders model scenarios: They stress-test assumptions, plan capital needs, and use financial models as operating systems to build investor confidence.

Answers to The Most Asked Questions

-

A startup financial model should include revenue drivers, cost of revenues, operating expenses, cash flow, runway, capital needs, and scenario planning.

-

Investors use financial models to assess growth quality, margins, capital efficiency, runway, and whether the founder understands how the business actually scales.

-

CapEx builds long-term assets like product or infrastructure, while OpEx covers daily operating costs. CapEx strengthens valuation, OpEx impacts short-term profit.

-

Runway is calculated by dividing current cash by monthly net burn. The model must also show milestones achieved before cash runs out.

-

An investor-ready model is logical, driver-based, benchmarked, defensible, scenario-tested, and clearly connects revenue, costs, margins, cash flow, and capital strategy.